LISTEN TO THIS ARTICLE:

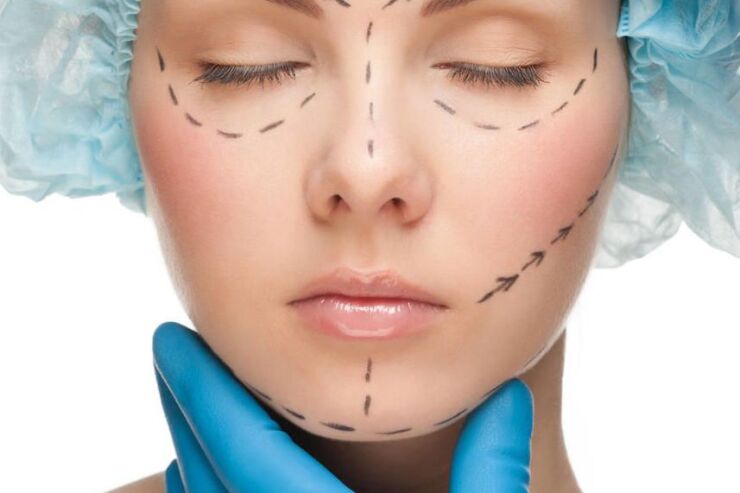

Cosmetic procedures in teenagers are rising at alarming rates. In 2020, teenagers underwent 229,740 cosmetic procedures, including almost 88,000 cosmetic surgeries. These were all done with the sole intent of improving appearance. This is a concerning trend at an essential period of growth and development.

The top five cosmetic surgical procedures US teenagers desire most are rhinoplasty, breast augmentation, otoplasty, eyelid surgery, and cheek implants. Rhinoplasty entails reshaping of the nose while otoplasty alters the shape, position, or size of the ears. The most popular, less invasive procedures teenagers seek are Botox, laser hair removal, laser skin resurfacing, laser treatment of leg veins, and soft tissue fillers.

Teenager social media use and cosmetic procedures

The rise in teenagers seeking cosmetic procedures in the United States is likely due to a combination of developmental, sociocultural, and psychological factors. The teenage years are a period when peer acceptance, the beginning of sexual relationships, increased emotional reactivity, reward seeking, and identity formation are central to adolescent development.

Teens seek acceptance from others and are hyper-focused on their personal appearance. As a result, adolescence is a high risk period for the development of body dissatisfaction. The vulnerability of this period is exacerbated through chronic exposure to social media. These platforms are a major place where teenagers absorb information about ideal beauty image standards and compare themselves to their peers.

About 95% of teens have a smartphone and 97% use the internet daily. The top five social media sites teens use are Youtube, TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook. Worryingly, according to the Pew Research Center, 35% of teens engage with one of these five applications “almost constantly.”

Destructive online behavior

Much of the drive for cosmetic procedures in teenagers may be coming from their experiences on social media. On these sites, teens perpetually view misleading advertising that uses airbrushed or digitally enhanced images, promoting an unobtainable beauty ideal. Moreover, girls are highly impacted by growing up immersed in a culture that sexually objectifies the female body. They learn from a young age to be critical observers of their own bodies. Thus, it is not surprising that females comprise 92% of all cosmetic procedure patients.

Sadly, 3 out of 5 teenagers have been bullied or harassed online, further damaging their already fragile sense of self. Bullying leads to poor psychological outcomes, including an increase in depressive symptoms and suicidal thinking. Teenagers who are bullied are more likely to seek cosmetic procedures than those who are not. This perfect storm of heightened vulnerability during adolescent development and the negative consequences of habitual social media use has led to a rise in body image issues and mental health conditions, such as depression, disordered eating, and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

People with Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) have a distorted body image and preoccupation with a perceived defect in one’s physical appearance that leads to impaired functioning. Body Dysmorphic Disorder often occurs during adolescence, with more than 70% of cases presenting before the age of 18. It is characterized by excessive mirror checking, skin picking, and frequent grooming. They frequently compare themselves to others, need reassurance related to their perceived flaws, and believe that others are equally bothered by their appearance.

BDD comes on due to numerous factors, including abuse and bullying during childhood. One study reported that 69% percent of patients with BDD were bullied at some point in their lives, leading to low self esteem. It comes as no surprise that social media use can play a big role in BDD as well.

BDD and cosmetic procedures in teenagers

In severe cases, individuals with BDD become very depressed and anxious. They may socially isolate themselves from friends or loved ones and perform compulsive behaviors, which can include self-mutilation – also referred to as “do-it yourself-surgery.” Others seek unnecessary cosmetic procedures as a solution with the belief that it will fix internal and interpersonal issues.

Although the data varies, studies suggest that 5-15% of teenagers seeking cosmetic procedures have BDD. Procedures performed by board-certified physicians are of course safer than self-performed surgery. However, it is necessary to question whether cosmetic procedures are a healthier alternative to self-mutilation or a consequence of the same untreated mental health issue.

Short-term and long-term implications

The long-term implications of cosmetic procedures are not well understood. Few studies have explored the long-term effects of cosmetic procedures in teens. However, we do know that adolescent bodies continue to develop until the mid-20’s.

The physical and hormonal changes that the teen body undergoes are complex. This can alter the results of specific surgeries, especially those pertaining to reshaping the nose or breasts – two of the top five surgeries that adolescents seek. The nose does not fully develop until 15 or 16 years in women and 16 or 17 years in men. Breast augmentation should be avoided until at least the age of 18 when full breast development occurs and hormonal fluctuations are not as prominent.

In mental health terms, cosmetic procedures in teenagers will not treat the root cause, whether it’s poor self image or a more severe condition like Body Dysmorphic Disorder.

Physician responsibility around cosmetic procedures in teenagers

Healthcare professionals have a duty to uphold the ethical principles of medical practice and that comes into play when teenagers seek cosmetic procedures. Physicians should educate teenagers about the risks of the cosmetic procedure and explain how the long-term effects are largely unknown and not well researched.

Most importantly, physicians should screen and assess for mental health conditions. If any signs of BDD or another condition show up, patients should see a pediatric mental health professional. Finally, if a patient is still interested in cosmetic surgery after being counseled, physicians should implement a designated amount of time after the initial consultation for further reflection.

Studies recommend a “cooling off period” of three months before any final decisions are made. This can help prevent people from making impulsive decisions that will affect them the rest of their lives.

Parenting tips around teenagers and cosmetic procedures

1. Self-Reflection

Check your own biases. Does your initial reaction come from a place of anger, fear, excitement, or sympathy? Saying “no” in a harsh tone to punish your child or “yes” in a sympathetic manner to temporarily improve their self esteem will not benefit them. Rather, it may shut down necessary future communication about the topic.

Instead, ask for some time and space to reflect in order to further develop your perspective about cosmetic procedures. Think about your own body image and insecurities. Explore how these feelings may be impacting your initial “yes” or “no” response.

2. Approach with Empathy

When talking with teenagers about cosmetic procedures, put yourself in their shoes. Identity formation and peer acceptance are central to their developmental needs. In addition to the negative implications of cosmetic procedures, acknowledge that self expression and “fitting in” are important factors for them.

What may seem trivial and unnecessary to an adult is actually a desire rooted in a fundamental need of a developing adolescent. On the other hand, what may seem like a good way to help your child “fix” their appearance and self esteem may actually harm a child’s long-term physical and mental health. Try to avoid being dismissive or overly encouraging of their desire to have cosmetic surgery.

3. Ask Questions

It is important to get to the root of what is driving your teenager’s motivation to have cosmetic surgery. Try asking thoughtful questions but do your best to avoid too many that begin with “why,” which can sound condescending and accusatory. Check your tone and inflection. Keep a calm voice with an even rhythm.

4. Listen and Paraphrase

When talking with your teenager, listen to understand rather than to respond. While you may be eager to “tell” your teenager how they “should” feel about cosmetic procedures, avoid this strategy.

It is important your teenager feels heard and understood. Repeat back what they said. Using the paraphrasing technique will help them feel heard and give the opportunity to re-explain something that you may have misinterpreted. If you find that either person is becoming upset, agree to take space and return to the conversation at a later time.

5. Encourage Independent Research

Encourage your teenager to do their own research about cosmetic procedures and then set a time for a follow-up discussion. In addition to an increased need for social connection, adolescence is characterized by a period of seeking greater independence.

Giving your teenager autonomy to shape their own opinion about cosmetic procedures before imparting your views is an important step in the process. In the meantime, do your own research. Further educating yourself about the topic will help develop, clarify, solidify, or shift your own opinion.

6. Open Dialogue

Let your teenager speak first by asking them to explain what research they found about cosmetic procedures. Acknowledge the points that they made and thank them for researching the topic so thoroughly. Then, take the opportunity to educate your teen about the long-term physical and mental health risks by presenting your own credible research. Allowing this back-and-forth enables teenagers to feel like an equal rather than feel inferior during conversations.

7. Model Healthy Behaviors

Give your teenager time to reflect on the conversation and come to a new perspective on their own terms. During this time, remember that most of what humans, especially teenagers, learn is through subconscious messaging. Parents play an important role in influencing children’s body image through modeling specific attitudes toward bodies, making comments about appearance, and creating family food habits.

Limit your cell phone and social media usage. Clear out old magazines around the house that may be reinforcing an unhealthy and unrealistic standard of beauty. Ditch the scale. Model a healthy relationship with food and your own appearance. You have an opportunity to improve your child’s body image through your words and actions.

Protecting teenagers

While the advancements of modern cosmetic procedures are impressive, the rise in procedures performed on teenagers raises a critical question. What are the consequences of this creation, especially on an impressionable teenage population? Just because these cosmetic procedures are now possible is not reason enough to perform them, particularly during a transformational stage of growth and development.

People spent a staggering 16.7 billion dollars on cosmetic procedures in the United States in 2020 alone. There is something wildly unsettling about benefiting off of the insecurities of those bombarded by unrealistic beauty standards during an era where social media algorithms harm the mental health of teenagers.

The United States healthcare industry has an ethical obligation to protect, educate, and promote the physical and mental well being of this highly vulnerable population. Healthcare professionals and parents must proceed cautiously, weighing the benefits and risks of cosmetic procedures while taking care to ensure that the teenagers seeking these procedures feel supported by trustworthy adults.

Learn

Learn Read Stories

Read Stories Get News

Get News Find Help

Find Help

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share