Welcome to Psyched for Mental Health, the official mental health podcast of WebShrink.

In this episode, Alyssa Peckham, PharmD discusses harm reduction for substance use. What is harm reduction and how can it help save lives?

Transcript:

The following is not intended to provide direct medical psychiatric, or substance use treatment advice, and is not a substitute for evaluation and treatment by a healthcare professional.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Hello. I’m Dr. Ed Bilotti. And this is Psyched for Mental Health, empowering you with trustworthy information about modern psychiatry. This podcast is a companion to WebShrink.com, THE platform for seekers and providers of mental health care.

Today, we’re going to be discussing the topic of harm reduction. What is meant by harm reduction? Seems straightforward enough. Reduce harm. Every day each of us goes through our day attempting to reduce harm in just about everything we do. I pick up my coffee mug by the handle, so I don’t burn myself or drop it because it’s too hot. I take my bagel out of the toaster using wooden tongs, so I don’t get burned or electrocuted.

Driving to work, I put on my seatbelt, and my car is also equipped with all kinds of safety features and technology to hopefully prevent me from dying in a car crash before I make it to the office. I could just stay home and hide away from everything and take absolutely no risks at all, that would reduce the likelihood of harm to a minimum, but then I would accomplish nothing ever.

And what would be the point? Frankly, how long could I survive that way?

So, harm reduction is something we all do all the time, but how does this fit within the context of substance use? Though it’s been overshadowed for the past couple of years by the COVID pandemic, America continues to be in the throes of an opioid epidemic. The opioid epidemic has not gone away. In fact, provisional data from the CDC website and the national center for health statistics, show that for the 12-month period ending April 2021, there were an estimated greater than 100,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States, nearly a 30% increase from that same period the prior year.

Now, if we truly understand addiction and substance use, it should come as no surprise to anyone that use actually increased during the pandemic as people became more isolated, worried, and depressed. So, in spite of states cracking down on prescriptions for opioids and ongoing efforts to stop drug use, it continues.

Throughout history, humans have always sought out mind altering substances. It seems they always will.

My guest is Alyssa Peckham, a Doctor of Pharmacy who has specialized in psychiatric and substance use disorders. Alyssa shared her insights about harm reduction in a piece published on web shrink. And today I have the pleasure of speaking with her to explore these ideas further.

Alyssa, thank you for joining me.

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Thank you for having me.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

So, you have a somewhat unique background. Can you tell us a little bit about how you got into this field and what’s your background and training?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Sure. I am a pharmacist by training and in becoming a pharmacist, there are a couple of different specialties that we can choose from. I chose psychiatry and addiction. So, in doing that, I was required to do postgraduate training in the form of residency and fellowship. And so, I completed that down at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Connecticut, in partnership with Yale New Haven Hospital. And then once that’s completed, you’re eligible to sit for your boards.

So, I’m a board-certified psychiatric pharmacist.

My interest in the field was really born out of just life experience. And so, I had family members that struggled with either significant mental health disorders or even some with various substance use disorders. There was a portion of my life where I didn’t quite understand those. And I think that probably resonates with a lot of people, right? You know, a lot of our opinions about substance use disorders and alcohol use disorder for example, are really born out of what we hear in the media and in movies. And so, my opinions in my youth at that time were that these were family members that I didn’t want to be associated with. And they made poor decisions for example, and I really wanted to understand that better, you know, nature versus nurture. Is it a combination, kind of what is driving those illnesses?

And so, I really was inspired by people in my immediate family to learn more about that. And once I started to study this and get into the field and, of course, understand in much greater detail that these are chronic illnesses that undoubtedly deserve access to healthcare resources and, you know, specialized care, like any other disease. I also was exposed to how much we do not care for this population, how much of a lack of resources there are for them and how stigmatized and marginalized this population is.

So not only was it learning about the disease states, but it was also learning about the unmet need that really was there for this population. And so I knew right away that that’s something that I wanted to specialize in and do for, you know, the rest of my career.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

I don’t think a lot of people understand the training of pharmacists and that pharmacists actually do a residency and that pharmacists specialize in different areas. You know, most people just sort of think of the pharmacist as that person up on the elevated platform at the local CVS.

There’s so much more to it right?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Right, yeah. And you don’t have to specialize, you don’t have to do a residency. So certainly, after you complete that six-year doctoral program, you can go right into practice. And we’ll oftentimes see that in our community partners at places like CVS, Walgreens, maybe some independent pharmacies. And you can also go right into hospital practice. And so, there are hospital pharmacists that, you know, exist within our hospital systems. I think sometimes we forget about them, but they’re oftentimes behind the scenes really making sure that the medications that are entered by prescribers are correct and safe. And then once those are approved, they go up to the floors for nursing to administer. So, we’re not really seen all the time, but we are starting to get more integrated into healthcare teams.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

I remember even in my training as a medical student and a resident back in the eighties and nineties, having pharmacists in training on morning rounds with us, actually seeing patients and discussing cases. And I guess with the growing abundance of pharmaceutical agents, it’s impossible for any one person to know everything about every drug. And so having that additional member of the healthcare team can be a huge help.

So, in terms of harm reduction, In the context of substance use, what is it? Is it a philosophy?Is it a treatment approach? Is it an intervention?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Well, harm reduction really can be applied to, you know, a lot of different things, a lot of different areas, even internal, external to medicine, but harm reduction really in its simplest terms, it’s just any kind of steps that are taken to. Essentially reduce harm from a potentially harmful activity.

So, we’re talking about substances today and harm reduction is really anything that’s done to reduce that substance related harm and the key word there. And you kind of already alluded to this, the keyword there is that it’s anything done. So that doesn’t mean abstinence. That doesn’t mean sobriety. That doesn’t mean cold turkey. That doesn’t mean we keep doing what we’ve been doing because it hasn’t been working, right?

It speaks to a much larger, you know, a much more comprehensive set of behaviors. And you mentioned, you know, is it a philosophy? Is it an intervention? And, you know, my answer is it’s, it’s most certainly both.

When we think about the root of philosophy, that’s, you know, kind of seeking fundamental truths, right? And you know, the truth behind harm reduction is that people have a right. You know, people have a right to medical information to safety information when they are seeking that. People have a right to know how they can avoid these potentially harmful medical situations.

When we talk about a treatment approach or an intervention, it is that as well. And so, when you know, someone is using substances, whether that has progressed to a substance use disorder or not, if abstinence or sobriety, or a reduction in substance use is not an immediate goal, that’s when we change our treatment approach, we change our intervention to say, okay, what are your goals and how can I meet you where you are? How can I kind of…

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

When you say not an immediate goal, you mean not an immediate goal of the individual, not of the treatment provider? So, it’s not the individual’s goal to reduce or abstain from using substances. So, then what do we do then? How can we help? Is that what you mean?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Yeah. Yep. That’s exactly what I mean. Thank you for clarifying that. So, when we’re engaging, if it’s a healthcare professional, or maybe a loved one that cares about this person, when we are engaging in conversations around something that is potentially harmful, which in this case is substance use, we always want to find out, what is motivating that substance use? What is your desired relationship with that substance use? Right? That could be abstinence, but maybe it’s oh I wish I just used a little less or in social settings or whatnot, you always want to find out why they, why they’re using, what their desired relationship is, and how can I get you there?

And so, when I say not an immediate goal, the individual might not identify sobriety as a goal might not identify abstinence as a goal and, as a society I think we have to start accepting that that as an option. And that is okay. Much to what you said earlier in that what we’ve been doing just it’s really not working.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

So, in other words, if the goal is not abstinence or even necessarily using less than the best way to help someone who’s at that stage is to. Help them find ways to be able to keep doing what they’re doing, but cause themselves less harm?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Less harm. Right. Exactly. And so, harm reduction really takes a lot of different forms and that can depend on the substance and on the route of use. So, if you start with something like snorting substances, for example, so snorting cocaine, and I’m sure we’ve all seen, you know, in the Hollywood movies, the rolled-up dollar bills, or maybe people have seen that out in the wild, when they’re doing what they’re doing in the social scene, dollar bills, as we know, can carry a ton of bacteria. And so, if we’re using that as a vehicle for cocaine entry, into our nasal passages, that can introduce bacteria into an area where It’s really not supposed to be. And with repeated use of cocaine, we can get some erosion on the inside of our nose. And so, when we introduce that bacteria, we can get into a pretty difficult situation.

A simple harm reduction measure is to use an unused straw right out of the package or right out of the paper. So that is something that would be considered safer to use in that situation.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

If I can kind of play devil’s advocate here because trying to put myself in the shoes of someone who might be thinking about this whole thing a little bit differently, hearing what you just said, might say, aren’t you just encouraging someone to use drugs then? I can’t believe you just gave somebody a way to snort cocaine that’ll work better for them than using a rolls up dollar bill. How can you do that? Right. I mean, because using drugs and alcohol is inherently harmful, so isn’t it the goal to stop people from using them at all?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Well, inherently harmful is an interesting term. It means that something is still dangerous despite taking the necessary precautions. And we can draw a lot of parallels there, right? So, we can say that driving a car is, you know, pretty harmful, inherently dangerous. We can say bungee jumping, right? Not something that everybody does, certainly stepping up the ladder of being inherently dangerous, but. We’re careful. We seek expert guidance. We make sure that there’s a, you know, an area in which that can occur. Does everybody bungee jump? No, but maybe some people like that feeling and are kind of interested in that experience, and substance use can be a lot like that. So, do we have to resort to prohibition? Do we have to resort to abstinence? Probably not, uh, we could just accept that substance use is going to occur, whether we agree with it or not. And instead, we bolster those harm reduction efforts to make it safer, not only for the individual but also the community. And there’s been a ton of research out there. That’s looked at various harm reduction interventions, spanning decades, and the results have been pretty consistent over time and overwhelmingly positive compared to, you know, what we do in present day.

I really like that you kind of brought up the skepticism of harm reduction, because that is always the first question that I get asked, or maybe other people that fall on this side of the harm reduction line get asked. And my answer is always, oh, absolutely. How could I, how could I blame anyone for being skeptical? Because we don’t talk about this. We only talk about the harms of substance use or, you know, quote unquote, only bad people are using substances or what have you, insert any kind of stigmatizing sentence that you’ve heard about substance use. And so, if we’re only ever talking about that side of the coin, then how can we be aware that there’s a-whole-nother side? Unfortunately, decades of this mindset have led us further and further down a path of stigmatizing this population, uh, marginalizing this population. And so, when we pre-plant those views that something is inherently bad and harmful then it makes complete sense to be skeptical because maybe we view this now as a radical approach. But I would really encourage listeners instead to follow the science rather than what you’ve heard. Follow the science.

I’ve mentioned it very briefly, but there’s more and more literature coming out, particularly amid the opioid crisis, that shed a lot of light onto how much of a demand and a need there is for harm reduction, how beneficial and life-saving this can be for individuals. We actually find that when we implement harm reduction in communities, we either find unchanged substance use or a decrease in substance use both at the individual level and in the surrounding community. Cause I think sometimes people get concerned, oh, you know, substance use is going to increase in my community. We have found either unchanged levels or decreased levels. We have yet to find an increase in new onset substance use or substance use disorders after harm reduction interventions.

Maybe that was a very roundabout way of going back to your original question of, are we encouraging drug use? The simple answer there is absolutely not. Absolutely not. The one thing that we are encouraging by offering harm reduction is repeated connection to maybe those harm reduction efforts are coming from a medical facility or maybe a harm reduction center, harm reduction specialists. We are encouraging, repeated connection and for people to keep seeking medical information and that’s one of the greatest aspects of harm reduction.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Do you mean so they keep coming back to the clinic or establish a relationship or a connection with a healthcare professional?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Yeah. Yep. That’s exactly what I mean, because harm reduction is not a one-time intervention and I’m so glad that you asked that it’s not a one-time intervention. It is interventions that can build upon each other, or it can be the same intervention that is implemented over and over again. And so, a good example of that is sterile needles and syringes. Something that someone is, if they’re continuing to use, they’re going to have to keep coming back to get new, safe supplies.

So, it promotes that repeat connection to whatever that is, medical facility, harm reduction specialist. So, harm reduction is really that safety net. If I’m the healthcare professional that’s sitting in front of them or I’m their family, I’m their friends sitting in front of them. Instead of leaving them without safe access to materials or without sharing knowledge of safer behaviors we have now increased their risk of harm because we know what’s going to happen.

Harm reduction. I think contrary to popular belief really does not sidestep or minimize the actual harm that can result from substance use. And so, transparency of risks and benefits, how we’re using certain substances when we’re using certain substances, it’s really a core component of harm reduction.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Recently, I was in a very unique situation at the office where I have my practice. There is a common hallway and restrooms that are shared with two other office suites occupied by businesses that really have nothing to do with healthcare or helping professions. And there’s a door leading to the outside, into that common hallway.

We started to notice some unusual activity in the restrooms. The doors were locked for a very long time, sometimes over an hour. And then. Someone heard sounds coming from in there. That sounded like there were multiple people in a single restroom and it came to light that there were people coming in from the outside, through that outside door that were likely homeless because they were carrying their belongings and one had a small suitcase. And they were using our restroom to use drugs. There was clear evidence they left behind that that’s what was going on in there.

One of the people that works in one of the offices across the hall became very aggressive, loud, screaming, yelling, cursing, name, calling, telling them to get out, get a job, speaking to them in a way that was just so dehumanizing and hateful.

Now as an addiction psychiatrist, where I spend every day, all day trying to help people just like this, it was a very awkward situation for me to be in, but it was interesting for me to observe in real time the effects of stigma and how people are treated this way. And we see this in so many settings, even in healthcare settings, in emergency rooms and primary care offices, people are treated like drug seekers. Their medical problems are minimized or dismissed because they’re labeled as drug addicts or drug seekers.

Now to your point about developing a connection and keeping people engaged and coming back in my practice, I’m always struck by the reaction and the change in people’s affect. In other words, when they come in, they’re filled with shame and self-blame and self-loathing, and they’re clearly not feeling comfortable talking about their substance use or the fact that they may have relapsed. When I don’t respond with judgment or criticism. And instead, I respond in a way that is, let’s just try to understand what happened, why it happened. What would be the most helpful in terms of problem-solving here? I see an immediate shift in their facial expression and developing that trust is just so important in order to engage someone in treatment and help them make their lives better.

Had I reacted the way they expected me to react, which is the way most of the rest of their world has reacted to them, family, friends, healthcare providers, by becoming angry, judgmental, wave a finger in their face, punitively saying, essentially, you’ve been bad, you’ve done something bad. You need to clean up your act. And so on, really just breaks down any possibility of rapport, sends them out the door to go back and use again. As opposed to developing a trusting relationship where they can feel safe and engage, and ultimately greatly improves the chances of getting them to a point where they’re ready for making changes.

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Exactly. Right.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

So earlier you mentioned prohibition, clearly prohibition, and even more recently movements, like just say no in the 1980s, clearly these things were failures. Here we are in 2022 and we have continued problems, if not more problems with substance use. Can you speak to how prohibition just saying no, things like that, support the idea of harm reduction, as an approach, as an alternative?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Yeah. It’s, it’s an interesting point to make because you know, most anti- harm reductionists will turn to programs like that. Or I guess if you can call prohibition a program, but you know, programs like just say no, or movements like prohibition as alternative interventions to allowing substance use, but it is things like prohibition and just say no that actually completely exploited the need for harm reduction. So, these examples are actually used by harm reductionists and anti-harm-reductionists from two separate sides of the coin. Things like prohibition, things like just say, no, they really give people one option and one option only, and that is don’t use substances.

And I think anyone that’s, you know, lived on this planet for five days understands that no matter what type of regulations we have in place, Substance use will persist despite how tight that regulation starts to become. And we saw that during prohibition.

So, what happens now is you back people into a corner and you say, okay, we’re cutting off your sources of obtainment, right? So, you can obtain these substances in a safe way. You can no longer use them publicly, I guess we’ll say publicly referring to like bars. You can no longer use them publicly. And now we instill fear of punishment. Right. And so, what does that do? Well during prohibition, it really led people to start obtaining I’ll call it substances from unregulated sources, right? People are kind of home growers, so to speak, they’re trying to make their own supply. And that can be very dangerous to introduce impurities or things that our bodies aren’t supposed to be exposed to into the supply. Supply can get so low at times, despite being in such high demand, that it can lead to violence or some other kind of conflict.

And people start using trying to be smart about how they use, and will really start using, drinking during only certain times of the day or night, and that can lead to unsafe situations or kind of rushed use.

And that actually reminds me of the individuals that were using the bathroom space in your office. I, my heart just goes out to those individuals because where are they supposed to use substances in this world in the absence of safe consumption sites. And so, I’m actually glad that they found, you know, your free access bathroom in, in some way, because the alternative is behind a building somewhere exposed to the elements, or maybe they’d try to get into like a McDonald’s bathroom and then people are banging on the door so they’re rushing injection use, and that is so unsafe.

So that’s prohibition, but then in the just say no campaign, people were never given instructions for well, what if I said yes, what if I said yes and now I use substances? What now? Right? We never even considered that there was a potentially other way that people could respond to that question of using substances. And so, the use of drugs during that time was so highly stigmatized, uh, you know, in combination with that fear tactic, right? Of criminalization. People were actually, and still are in present day, very afraid to be transparent about their substance use. And that’s exactly what you just mentioned, right? People are fearful in your office of being transparent. They don’t know who you are. They don’t know if they can trust you because they’ve only ever experienced otherwise. Right? And people that actually approach them with compassion are unfortunately the minority.

Even though we have come so far as to recognize substance use disorders, alcohol use disorders as chronic health conditions, we still don’t really tell people how they can get help. We don’t find that in any other disease state, and it just, it blows my mind that we afford all of the healthcare services in the world to other disease states. Some still born out of, I guess I would say non-preferred behavior, right? Like sedentary lifestyle, poor diet management. Right? So, we do have some chronic disease states that result from behavior, but we give them access to resources. And we don’t see that with substance use disorders, things like prohibition, things like just say no are actually very classic examples of trying to force sobriety and abstinence and it not working. And then people are left unsafe without access to the information that they actually need.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Earlier, you mentioned you were going to give some examples of different ways that different substances are used and some specific kinds of advice that you might give somebody to reduce harm. You gave the example of snorting through a dollar bill. Are there other examples, like that?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Oh, yeah, there are tons of interventions. Again, it depends on what the substance is, and it depends on the route by which they’re using that substance. People can smoke drugs. People can inject drugs, drinking alcohol, right? That’s certainly a form of substance use. There are tons of things.

Just kind of running down that list. If someone’s using drugs by smoking, right? Like let’s say smoking crack. Well, there are actual supplies that usually you need to acquire in order to make that happen. One of them being a pipe. So, one of the simplest interventions is to make sure that you and you alone are using that pipe because when we’re sharing pipes between other people, not only is that transferring bacteria back and forth, but that can actually lead to more severe infections as well.

If people have cuts around their mouth or whatnot, that’s introducing another source of infection. So that’s unsafe. Um, and something that harm reduction intervention could provide. Sterile pipes, individual pipes for everyone. And another thing is too, when using crack, there has to be some kind of flame that is going to be applied to the end of the glass pipe and even distribution of the flame is something that, you know, people are usually surprised by that because if you just hold it you actually can destabilize the glass, which the next time you go to use, or maybe not the next time, but the next couple of times that glass can actually explode. And now we have risk of injury from the glass explosion. Right? So simple things like that. Just make sure you move the flame back and forth so that we’re not really overheating.

Injection use is probably the biggest focus of harm reduction right now. Um, you know, particularly amid the opioid crisis, which is so, so heavily dominated by illicitly manufactured fentanyl. Harm reduction efforts here could really include something like the practice of one needle, one injection. Meaning that someone has access to a sterile needle for every new injection that is going to occur. And this includes avoiding reusing your own needles. Sometimes people are like, oh, well, I’m the only one that’s used it. That doesn’t quite matter because in the time since you’ve last used that needle, there can be a lot of bacteria gathered on the end of that needle, which we’re now reintroducing right into our bloodstream. And on top of that, it doesn’t look like it to the naked eyes but on a microscopic level, that needle is actually getting bent more and more with each use, which can really damage your veins over time.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

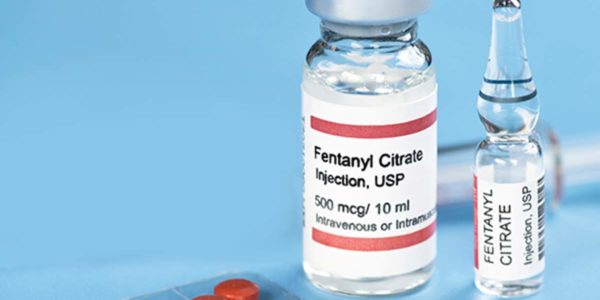

Can I just interrupt you there for one second before you go on to the next one? Can you talk about fentanyl? So, fentanyl is a hundred times more potent than heroin, as I understand it. Can you say a little bit more about what you mentioned about the illicitly manufactured fentanyl and what that is and where it’s coming from?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Yeah, so, and I think that’s something too that has certainly contributed to stigma of opioids in general, as prescription medication. So, every prescription comes, every medication comes with some kind of risk, some greater than others. Opioids certainly fall on, you know, a little bit of that greater risk end. However they can be safely used when they’re prescribed and taken appropriately under the guidance of a healthcare professional.

Fentanyl is actually a prescription opioid, but we hear a lot about it in the news. And that’s because it is the main driver of the opioid crisis, but not the prescription kind. The prescription kind is very different from what’s being used on the streets, which we are referring to as illicitly manufactured fentanyl, because that’s exactly what it is.

It’s being manufactured overseas in these homegrown labs, makes its way into this country, cut with a whole slew of substances, some benign, some quite harmful to our bodies. And that’s, what’s being used. That instills a lot of stigma that opioids are inherently unsafe because they hear the word fentanyl, and then they make the connection between prescription products. But it’s really this completely unregulated source that’s being shipped in from, from overseas. And as you mentioned, it’s much more potent than heroin.

We’re actually in the third wave of the opioid crisis, which is being dominated by fentanyl. The second wave was heroin, and the first phase was prescription opioids. So, it’s another point to make that a lot of people want to be protectors of, of opioid prescriptions. And that practice is, is wonderful, but there is a point where it goes too far, and it actually prevents access to medications that people need. And on the other hand, we really have maximized all of the efforts that we possibly can do to regulate opioid prescriptions.

We have to start keeping up with the times and the times are illicitly manufactured fentanyl, which is primarily being used either by snorting or injecting. So that goes way beyond prescription opioids. And again, this is another entry point for harm reduction.

If people are, you know, for the primary substance that’s being used, which is fentanyl, if the majority of people are injecting, we have to meet them where they are. And we have to start introducing some of the harm reduction.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

And it only takes a very tiny amount of fentanyl for some people to, even to, just, to, to actually kill them, right? It can be fatal from an overdose.

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

It’s hard to quantify, you know, what, what that amount is because everyone inherently has their own tolerance levels or, you know, baseline opioid exposure. But I think the main message there is that if someone back when we were changing over from heroin to fentanyl, it’s almost exclusively fentanyl now. When we were changing over, they both look like, you know, white powdery substances. And so, if someone goes to, to use the same physically looking amount of substance that they believe is heroin, and it’s actually fentanyl, you’re taking a hundred times more drug than you were before. And that is most certainly going to lead to an overdose and it probably everybody. And so, it’s, it’s very dangerous.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Absolutely. Is there a way that people can tell, is there a way that people can identify to be sure what they’re, what they’re taking?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Just by looking at it probably not. There’s always some people, if they’re visually inspecting their substances, like in the example of pressed pills. So, there are manufacturers out there that have gotten, I don’t want to say regulated manufacturers, there are street manufacturers out there that are so highly skilled in the way that they create their own that it actually looks very, very similar to prescription products and to the naked eye it’s really difficult to tell, and that’s why we encourage testing of substances.

And there’s a lot that goes into testing of substances, but particularly testing substances for fentanyl or unintentional fentanyl exposure. So perhaps there’s fentanyl in a cocaine supply or whatnot, you cannot really differentiate the two. So, testing all substances for fentanyl with fentanyl test strips is probably a best practice at this point.

You might be able to locate some test strips from a local harm reduction facility or, or a medical facility, but that would really honestly be the only way. And it’s, that’s unfortunate. So, in the absence of fentanyl test strips, we always encourage that someone does kind of like a test dose before. So don’t go right to the full amount that you were going to use. Just do a very small amount, see if it feels different. Did you get the effects that you were thinking of, or did it feel different? If it did then maybe kind of back off of that supply and get some help and see what you can do.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

A simple little test like that could save a lot of lives. How about alcohol, any harm reduction measures related to alcohol use?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Harm reduction efforts related to drinking really could take the form of designating a sober driver. Right? I think a lot of people use that practice, setting a limit for yourself, with how much you wanted to drink that day or that night, and then being careful to measure drinks so that there’s no overpour so making sure you have the shot glass or the jigger that you can use to measure drinks or whatnot, um, things like that.

So those are. Simple harm reduction measures that we probably already do in our day-to-day life. And you have to remember at the end of the day, alcohol is a substance as well. It is altering brain chemistry in very similar ways that opioids are. It’s interesting that society allows for regulated use of one substance yet, um, not another, neither with medical purpose. Right? So, it’s just interesting that one is so regulated and one is so not, and we accept harm reduction interventions for one, and we do not for the other.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

It’s interesting. And like so many things, it doesn’t make any sense. There’s no logic to it, right? Do you have any thoughts on the legalization of marijuana, first for medicinal use and then recreational use? In many states, and it’s really become, there’s kind of an explosion of easily available cannabis products, whether it’s THC or CBD and harm reduction doesn’t have a lot of application here because using marijuana doesn’t have nearly as many risks or dangers as some other substances, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have any. And again, this is also an unregulated industry, right? So, people don’t know exactly what they’re getting or what they’re smoking, what they’re inhaling. What are your thoughts?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Yeah, it’s, it’s a tough question to answer because I think we’re doing things well, and we’re doing things very unwell at the same time. So, I will say that I don’t have a blanket thought or answer on the explosion of the easily accessible cannabis products.

But what I do know is that it is scientifically backed that, you know, there, it may be useful. There may be some properties in there that are useful for, you know, various conditions that can range from psychiatric illnesses, which is very applicable to what we’re talking about today, but also things like skin conditions or cancer or whatnot.

But I think the biggest problem is that we did not come up with a regulation. We did not come up with a great regulation process prior to legalizing access. So, we don’t have central regulation of these products. We do have third party companies that can provide some kind of certificate of analysis, which is really just a certified lab that gives essentially tests results, right?

That confirm, uh, potency and purity of the product as it’s being advertised. But companies can actually opt out of this practice, so they don’t have to get, they don’t have to seek that certificate, um, if they don’t want to. And so therefore it’s a mostly unregulated process, so it should certainly come with a buyer beware warning, I guess I would say, um, you know, and if anything, look for that certificate of analysis on these products and, you know, ultimately consult a healthcare professional to determine, you know, the types of products that may be better suited to treat certain conditions if it’s medical.

Harm reduction certainly can still apply here. And, you know, we talk about the range and the way in which you can get cannabis exposure or CBD or THC exposure. And so, one thing could be instead of the smoking products. Cause I think in general, lighting something on fire and inhaling it, it’s probably not, not good for us. So instead of smoking, can we switch to a safer route of administration, whether that’s gummies or drops depending on what the desired use is.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

And I think it would probably be easier to measure a quantity of ingredients. And how much you are actually taking. When you talk about using marijuana medicinally, it’s really not because it’s kind of just use whatever you want, whenever you want, however much you want, or however little you want, there’s really no prescription or dose or dosing schedule. But if you used drops or edibles, that would be easier.

What about combining different substances? I imagine there some harm reduction in that, for instance, canned beverages that contain both alcohol and a stimulant like caffeine there are clearly some dangers in combining different drugs. Using cocaine and alcohol together…

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

The danger there can actually show up in, in a couple ways. And so, one way could be that the substances that are being used together actually have an additive effect, a dangerous additive effect. And so, a good example of this is benzodiazepines and opioids is probably a well-known dangerous combination, but you know, both of these substances are really medications rather, right? They’re both medications that are considered to be depressants. And so, what we mean by that is that they can dampen the central nervous system and that can slow or stop breathing. Unfortunately, that’s not what we want. Right? That’s not the desirable outcome. So, if someone’s using a certain amount of opioids and they’re seemingly fine, and then the next time that they go to use and they combine that with a benzodiazepine that next time they could find themselves really in a, in a potentially overdose situation, because those effects are going to be magnified.

And so, when you’re using two substances, that potentially are going to be working on the same areas in the body, separate them so that you can. And the effects of one before you introduce the substance of another, we can’t do them both at the same time, because then we could find ourselves in a situation far too quickly of potential overdose.

But then to your point, we actually have another harm that can be introduced when substances have opposite effects. Because when that happens, one substance can actually mask the harmful effects of the other. And so, a good example of this, I mean, you made a good point with alcohol and it being combined with a stimulant, but a good example of this is cocaine and heroin known as a speed ball or speed balling. Since the effects of these substances are essentially opposites. One being a stimulant, kind of revving everything up, and one being a depressant, kind of turning everything down. You may not feel how on the opioid side, maybe how difficult it is to breathe, or you may not feel how rapidly your heart is beating or how paranoid you’re becoming or anxious or whatnot from the cocaine.

And so, this does not mean that your body is at an equilibrium and everything’s fine. It just means that one substance may be preventing you from being able to notice the harmful effects of the other. And so, people might take more of one substance thinking that, oh, I don’t, I don’t feel anything. I feel fine. And then, you know, again, we have, we have an overdose risk.

So, separating use of substances is always going to be the best bet so that your body can adjust to and understand how it feels when one substance is present versus both. Obviously avoiding combinations of substances is probably the most desirable outcome, but again, it is likely going to happen in certain situations and so, we have to introduce safety measures.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

So, you’ve given us lots of techniques and interventions. Tell us what your personal experience has been like on the ground, working with people and how well received is this and what is it like for you to work with people using this approach?

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Part of my practice at a large academic medical center in the Boston area was to work in a low threshold, immediate access harm reduction, focused clinic. Part of that was, as I mentioned before, sometimes the only reason why patients came to clinic. So, they weren’t on medications for, you know, let’s say in the example of opioid use disorder, they were not on buprenorphine. They were not on naltrexone or, you know, we weren’t a methadone clinic, but they weren’t on methadone either. Um, they weren’t taking any medications, but they came for the harm reduction and they came for the education. And you could just see that they were getting a little bit better over time, a little bit better each time their faces got brighter. They felt safer. It was a good place for them. Sometimes we were able to provide them with food, with water. It was really just that human connection that you know, was really beneficial for them.

And I would say nine times out of 10, those patients eventually wanted treatment and were treated right there in our clinic and did very well. So, it just kind of goes to show how much that connection, um, means to people in a time where they’re not defining abstinence as a goal.

And that can be for various reasons. It’s not just, you know, I don’t feel like it today. There can be a ton of reasons that motivate abstinence or not.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

It must have been very satisfying for you.

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

The satisfaction on my end did not even compare to the satisfaction and the happiness that I know the patients experienced. And so, if there’s one message that I can leave with people, it is. We need to stop looking at people with substance use disorders, as you know, moral failing or moral misstep, because at the end of the day, they are humans that just live a lifestyle different than ours have behaviors and choices that are different than ours. And no one is perfect. And when we extend that human connection, that compassionate care, you’d be very surprised to see, you know, how happy and appreciative people are. And how much wellness can be achieved.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Alyssa Peckham, thank you so much for being my guest and for all of the insights and information that you’ve given us.

Dr. Alyssa Peckham:

Thanks for having me.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Thank you for listening. This podcast is a companion to WebShrink.com. Visit WebShrink.com where you’ll find original, trustworthy, and authoritative content to help you find the answers you need about mental health and addiction, mental health professionals, list yourselves in WebShrink’s provider directory, go to WebShrink.com and click list to your practice.

Learn

Learn Read Stories

Read Stories Get News

Get News Find Help

Find Help

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share