LISTEN TO THIS ARTICLE:

This is the second in a series of articles exploring doctor burnout, a quiet crisis that has been brought to light by the COVID-19 pandemic. Read the first article in the series here

From passion…

Doctor burnout has been on the rise for years, and COVID is pushing them to the limit. Next time you are at work, look around your workplace. Maybe you work in an office, a factory, a restaurant, a retail store, or a farm. Look at your co-workers and ask yourself how many of them are miserable right now? Not everyone likes their job, and few actually love it. In fact, about a third of Americans work because they need to pay bills, and they took the job they have simply because it was available.

It’s not all gloom and doom, though. At the other end of the spectrum, about half of people say they feel “very satisfied” with their jobs. Many begin a career with the expectation that they will put in some years at a less-desirable position first before moving up the ladder. This idea of progression is part of the definition of a career. You start in a place with opportunity for advancement, work hard, and then enjoy the fruits of your labor as you move higher up in your field. That’s the ideal scenario, and it’s very similar to the progression doctors go through: from pre-med to medical school, then residency, and finally to becoming a full-fledged attending physician. However, for a surprising number of doctors in America right now, and even well before COVID-19 hit, the satisfaction that should come with this advancement doesn’t last.

…To grind

Imagine that when you first started at your job, you loved it. You worked hard in training and invested a huge amount of your money, time, and passion into the career. But now, years in the future, all the late nights and long hours feel like a waste. A crushing bureaucracy with endless administrative tasks sucks away your time and energy. You have a massive debt from school and, although you make good money, each day it seems less worth it because of the immense stress and ever-increasing toll it is taking on you. You have little control over your work life and your connection to the most satisfying parts of your job has deteriorated because the system has stripped it away. Worst of all, you feel pressure from all sides with no available exit. Sometimes it seems like the “good money” you make is costing you everything.

Such is the plight of the burned-out physician.

Over two-thirds of all doctors in the U.S. experience burnout. Those hardest hit are primary care physicians (PCPs), 80% of whom are afflicted. You read that right, 80%.

The scope of burnout

So, just how many doctors are miserable? The short, scary answer is way too many. Over two-thirds of all doctors in the U.S. experience burnout, and those hardest hit are primary care physicians (PCPs), 80% of whom are afflicted. You read that right, 80%. These are frightening statistics. How well can a burned-out surgeon operate? How effectively can a burned-out psychiatrist diagnose mental disorders? And how can burned-out PCPs give enough attention to the hundred or more patients they see each week?

It gets worse. When you break doctors down by age, the youngest ones are at the highest risk of burnout. It strikes three-quarters of young doctors – those in their 30s and early 40s. Additionally, a third of doctors feel so poorly about their position that they do not feel the job is worth it and would not recommend others pursue it. This does not bode well for the future of medicine in America.

Burnout has become so widespread in the profession – and its impact so immense on the quality of our healthcare – that it is now considered a public health crisis.

Unwelcome changes

Burnout is so widespread in the profession – and its impact so immense on the quality of our healthcare – that it is now considered a public health crisis. Physicians attribute this to the huge changes that have taken place in the practice of medicine in America over the past four to five decades. Many people are not aware of how much American medicine has changed over this time, but it has, drastically. To understand this, we have to discuss the main points of the biggest evolution in modern medicine: the rise of managed care.

Ballooning costs

Throughout the 1980s, the cost of healthcare in America was skyrocketing. Over a 13-year period, national healthcare spending ballooned by 50% overall and even more in some places. The system that dominated then was a fee-for-service model, where healthcare providers billed insurance companies for each exam, test, or procedure. Health insurance was provided by employers (who took part of the cost out of employees’ salaries), and employees had a wide range of choices. There was almost no oversight, and few systematic cost-control measures existed.

The problem with the fee-for-service model is that it encouraged some doctors to over-test and over-treat. Any question about a patient’s health – however small the concern – could be addressed with more tests without regard to the cost. Patients wanted the best and the most of everything to feel satisfied with their care, and doctors wanted to provide that for them. Under the fee-for-service model, some doctors might perform simple services that could be done less expensively by other healthcare providers. That system was blamed for skyrocketing healthcare costs.

A hyper-complex system

In response, managed care offered a new way of paying for healthcare that promised to slow rising costs and incentivize more efficient use of resources. It was supposed to control medical costs by shifting how costs are estimated and how services are paid for. These changes were met with ire from physicians.

…originally intended to save money, the administrative burdens around this process have gotten so out of hand, they now account for hundreds of billions of dollars in additional healthcare costs every year.

To keep costs down, insurance companies have compelled doctors to keep detailed records of why patients are there and what care they are receiving. The insurance company then performs a “utilization review” before paying for the visit. If a doctor takes too much time or performs a test that the insurance company feels is unnecessary, they will refuse to reimburse the doctor, who then loses money.

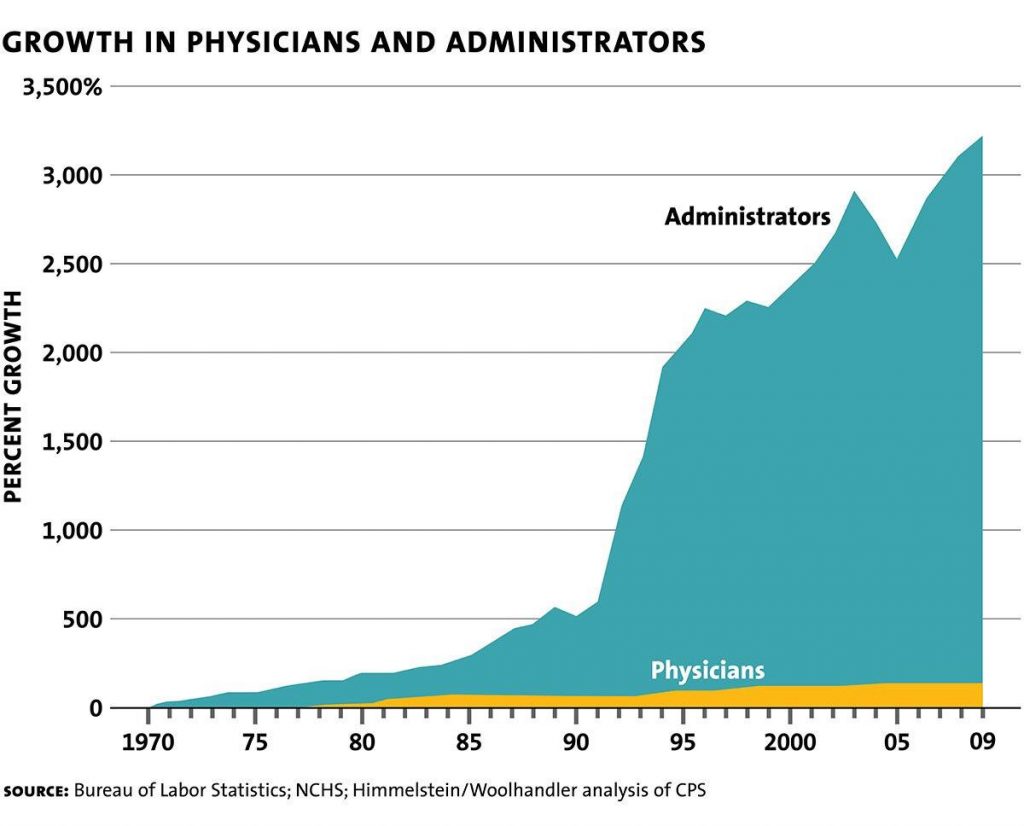

Though these measures were originally intended to save money, the administrative burdens around this process have gotten out of hand. They now account for hundreds of billions of dollars in additional healthcare costs every year. The difference now is that the additional costs are not going toward providing any care at all. Instead, they are going to administrators, bureaucrats, CEOs, and corporate shareholders in the form of huge profits. So, while the original intent was to manage costs, instead, what has happened is that costs have continued to rise, but more dollars are going to those whose job it is to prevent patients from receiving care.

Financial incentives…

The top-down approach produces a financial incentive for doctors to limit health expenses for patients – to test less, to treat less, and to spend less time with them. Insurance companies argue this decreases unnecessary tests and treatments, but doctors say it limits patient access and puts physicians in not just an uncomfortable position, but sometimes a moral dilemma.

Another model the managed care companies like is called “capitated reimbursement.” In this system, which is commonly used in primary care situations, doctors receive a set amount of money per patient per year. The idea behind this is that the patients who use fewer resources will balance out those who use more. This makes some sense when you think of patients in large groups, but it neglects the true individuality of medicine.

… Don’t lead to good medical care

The top-down approach produces a financial incentive for doctors to limit health expenses for patients – to test less, to treat less, and to spend less time with them. Insurance companies argue this decreases unnecessary tests and treatments. However, doctors say it limits patient access and puts physicians in not just an uncomfortable position, but sometimes a moral dilemma.

Imagine that you know there is a test that could tell you, with a higher degree of certainty, that your patient does or does not have a particular condition and, at the very least, relieve their anxieties about it. Your job as a doctor is to do exactly that. But your livelihood matters too. You have your own bills and a family to support. The insurance company has arranged it so that if you order this test, you are going to lose money. If something is missed and there is an adverse outcome, the insurance company bears zero responsibility or liability. It’s all on you. Imagine being faced with this scenario many times a day.

As with many things in this new healthcare world, doctors don’t have a choice. The implementation and use of EMRs has been forced upon them.

The Doctor is logged In

In recent years, the rise of electronic medical records systems (EMRs) and the intrusion of computers into every aspect of medical care have made matters even worse. EMRs brought the promise of fast, easy access to records. However, years into their widespread use, they remain cumbersome, convoluted, and difficult to use. Doctors almost universally detest them and would prefer to still use paper records. EMRs add complexity to note taking, turning what could be a single page of information into five or ten pages. They demand an enormous amount of a physician’s attention while their time is increasingly pressured. Additionally, unseen computer errors provide fodder for malpractice lawsuits and potential insurance denials.

So not only do they hinder doctors’ work, they have also become tools for the very organizations that doctors struggle against on a routine basis. As with many things in this new healthcare world, doctors don’t have a choice. The implementation and use of EMRs was inevitable.

Growing frustration

If managed care sounds extremely complicated, that’s because it is. Most Americans only experience our healthcare system as patients, where they feel frustrated to discover a murky landscape of bureaucratic red tape and ridiculous expenses. Anyone reading this likely has at least one exasperating tale. Surprise bills, back and forth with insurance companies, conflicting information from different people in the same healthcare network; the list of potential irritations is discouraging for everyone. Now put yourself in the place of a burned-out doctor working in that system every day. Burnout becomes almost inevitable.

The vast majority of doctors went into their field to provide doctoring – an art and science of care giving and healing from one human being to another. They now find themselves trapped in a system where that is essentially nonexistent. Doctors feel forced to function like automatons doing assembly line work and treating patients like widgets in a factory. They bear enormous responsibility and liability for their decisions, but very little autonomy and control over making those decisions.

Doctors feel threatened

Doctors are supposed to be the heart and soul of the healthcare system, but instead, they have come to feel threatened by it. They believe this new system devalues their opinions and distrusts their expertise. They have given years of their lives and thousands of hours to honing their skills, only for insurance companies and administrators to constantly challenge them. Their source of income (reimbursement for seeing patients) is constantly threatened, and they are forced to keep ultra-detailed records in their defense. Any slip up on their part could mean they will not be paid for their work, or worse. This, combined with the requirement to pack in more patients in less time and then spend hours entering data on a computer keyboard, creates an incredibly stressful work environment that plays a huge part in physician burnout.

What makes doctors happy?

Unfortunately, the system that was meant to solve problems, instead, created so many more. Managed care has interfered with almost every aspect of what doctors love about being doctors. For most, the best part of the job is the patients. Physicians want to be able to provide the best care possible without interference or constraints. They dislike paperwork, EMRs, and other office tasks that take away from face-to-face time with patients. Doctors resent intrusive, overbearing administrators. They don’t enjoy rigid time constraints or feeling forced to rush through seeing patients. They want a voice in making their own schedules and, like all of us, they need some work-life balance.

Doctors need their interactions with patients to be meaningful. Like all of us, they want to feel appreciated, and this includes being compensated well for their hard work. They also enjoy seeing the same patients over a long time in order to follow their progress and make genuine connections. They don’t like it when patients leave their offices unsatisfied, and they take complaints very seriously.

Changes brought about by managed care have threatened every one of these things. As a result, managed care’s dominance in American medicine has been met with howls of objection from physicians. This system not only added more complexity to physicians’ lives, but proved detrimental to their own satisfaction and ability to do their jobs in the best way.

Losing touch

What makes this even more difficult to comprehend is that, in America, the concept of personal freedom is paramount … Yet, with healthcare, our choices, and the information available to us to evaluate them, remain very limited; and these are choices that may ultimately affect how we live and die.

Physician surveys find that over 80% of doctors who lived through the changeover to managed care feel that foremost among its problems is the negative impact on doctor-patient relationships. The primary insult to the doctor-patient relationship has been the added time pressure during visits. Doctors constantly lament that they have less time with their patients. Many say they need up to 40% more time to provide the level of care they believe is appropriate. The pressure is to see more patients in a day, spending less time with each one. Furthermore, most doctors’ schedules do not provide time for the detailed documentation and EMR data entry they have to do. A third of doctors say they spend more than 20 hours per week on administrative tasks like this, and the hours grow every year. Very often they have to do these tasks after hours or on weekends.

Patients are unhappy

Patients don’t like it, either. Think back to the last time you saw a doctor and how much time she spent looking at a screen or typing. How much attention did you feel you were receiving while the doctor stared at a screen and rattled off questions? This is not the burned-out doctor’s choice. This is simply what they must do under the strict guidelines imposed by insurance companies.

The system gives doctors little power in deciding how much attention each patient’s issues can receive. Ultimately, it pits a patient’s needs against a doctor’s ability to generate revenue for the hospital or practice. Administrators pressure doctors to meet productivity quotas, which puts a major strain on doctor-patient relationships and diminishes quality of care.

Doctors spend years building rapport with their patients, only to be forced apart because a horde of faceless bureaucrats say so. This is not good medicine.

Less choice, less autonomy

Another major change in the healthcare system is a decrease in the level of choice. Under managed care, health insurers contract with providers (hospitals, primary care physicians, labs, specialist groups, and other healthcare providers) to provide services for patients who buy their insurance. If a provider or facility is out of the network, the insurance company pays less money or none at all. The patient must bear more or all of cost. This limits the patient’s choice for what care they can get and from whom. Additionally, it limits the doctor’s ability to recommend the best course of action because they need to take into account the patient’s capacity to pay. No one is happy here except for the insurance companies who are reaping profits from these arrangements.

Such lack of choice directly interferes with patient autonomy. That’s a patient’s ability to make choices about their medical care without being inappropriately influenced. Limits on which doctors or which treatments an insurance plan will pay for restrict patients’ freedom in making decisions about their health.

No choice

What makes this even more difficult to comprehend is that, in America, the concept of personal freedom is paramount. Advertisers bombard consumers with vast amounts of information about different cars to buy, foods to eat, and places to visit. We can compare our options and make educated decisions about what we want to buy. Yet, with healthcare, our choices, and the information available to us to evaluate them, are very limited. These are choices that may ultimately affect how we live and die.

This dismal irony is lost on no one. Doctors are champions of their patients’ health, and they see people’s frustrations with the system firsthand. They must only prescribe medications that the patient can afford. A primary care doctor must only refer patients to specialists in their insurance network. If someone’s insurance changes, they may have to change their primary care physician. Doctors spend years building rapport with their patients, only to be forced apart because a horde of faceless bureaucrats say so. This is not good medicine.

This is the only industry where you have to buy a product before you find out how much it costs.

Hidden costs and surprise bills

Not only is information about healthcare choices limited, but potential costs are vague as well. Managed care has created a situation where there is very little transparency about what services will cost. Have you ever asked what something costs at a doctor’s office or a hospital? No one will be able to give you a straight answer. They always say, “We have to process your claim to find out what the coverage is.”

This is the only industry where you have to buy a product before you find out how much it costs.

If you haven’t personally experienced the horror of receiving surprise healthcare bills, there’s a good chance you know someone who has. Imagine you get in an accident, and the ambulance rushes you to the emergency department of a local hospital. Weeks later you receive an unexpected bill for thousands of dollars. Although the hospital was in your network, a provider that saw you was not, and you didn’t find that out until it’s too late.

Doctors just want to do their jobs

To be sure, doctors dislike this system as much as patients do. When a doctor walks into the room to see a patient in need, they don’t want to stop and make sure they are in that patient’s network. That’s not even on their minds. The only thing doctors (and patients) want to focus on is the patient’s condition and care. Imagine realizing a doctor is out of a patient’s network and the patient must delay treatment to find a doctor they can afford. This potentially puts lives in jeopardy over dollars and cents. There is no easy way to verify costs, so the problem continues. In the end, the patient foots the bill, and doctors feel frustrated that they remain stuck in a broken system that penalizes everyone but the insurance company.

Some doctors are happy to be employees because it relieves them of the headaches of business ownership. The problem is that employees must do things according to how their boss wants them done. And in most of these employment situations, the bosses are not doctors at all. They are administrators with very different goals and priorities than doctors. Doctors, like any of us, don’t like being told how to practice their profession by someone who does not have the training and expertise they do.

The disappearing private practice

The administrative burdens brought on by managed care have also had a major impact on the tradition of small, physician-owned practices. As demands around billing, record keeping, and use of expensive EMR systems got more complex, the overhead cost of running a doctor’s office increased dramatically.

This has led many private practices to sell out to their local hospitals or other large healthcare organizations. This has created a small number of large hospital networks. This consolidation has caused a major shift where many doctors are losing their status as independent business owners and becoming employees. In fact, 2019 marked the first year ever that more doctors were employed by hospitals rather than doctor-owned private practices. It’s no accident either. Insurance companies prefer to negotiate in board rooms, between high-level executives and administrators. They don’t want to deal with individual doctors, who know the value of what they do and are likely to at least try to stand up for it.

The average hospital CEO makes twice as much as the average general physician. But who sees the patients? Who comforts grieving families? Who saves the lives?

Doctors as employees

Some doctors are happy to be employees because it relieves them of the headaches of business ownership. The problem is that employees must do things according to how their boss wants them done. And in most of these employment situations, the bosses are not doctors at all. They are administrators with very different goals and priorities than doctors. Doctors, like any of us, don’t like being told how to practice their profession by someone who does not have the training and expertise they do. Decisions about care should remain between a patient and their doctor.

In a hospital setting, many administrators are not physicians, but they hold power above the doctors employed there. Doctors resent that people with no medical training or degree and no experience caring for patients can dictate how they practice medicine. This can include things like how many patients they must see, what medications they can prescribe, and whom they have to work alongside.

Who’s really making money?

Most feel surprised to discover that the highest paid people in hospitals are the administrators, not the doctors. The average hospital CEO makes twice as much as the average general physician. But who sees the patients? Who comforts grieving families? And who saves the lives? Who produces the cumbersome medical records so the hospital can get paid? And who carries the legal liability and the emotional burden if something goes wrong? The doctors. Yet administrators are paid more every year while the threats to doctors’ incomes continue.

The modern American medical system seems to not only ignore the reverence that was once reserved for doctors, but to systematically and purposefully erode it.

Cogs in a machine

Doctors, as a whole, feel burned out – exhausted from the long hours they spend rushing from patient to patient. They’re exhausted from the mountains of paperwork and hours of typing into EMRs. They feel trapped in a chaotic and broken system that they cannot change. Traditionally, doctors felt accustomed to having autonomy, and rightly so. No one else in our society is imbued with the immense privilege and responsibility of doctors. They can lay their hands on others and are entrusted with deeply personal parts of their patients. But the modern American medical system seems to not only ignore the reverence that was once reserved for doctors, but to systematically and purposefully erode it.

The introduction of the term “provider,” now widely used, diluted the status of the title “doctor.” Expanding the scope-of-practice and independence of nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants created confusion for patients by generalizing them and doctors all under the term “provider.” This then allows the insurance companies to pay less for care when those who deliver it have less extensive training and expertise than doctors.

Time is money

A physician’s time is now a commodity, a product to be sold. However, they have less and less control over how this happens. Insurance companies and hospital administrations pull the strings of this puppet show. They decide how hard doctors must work and whether they get paid. Of course, they take their cut, which is now significantly greater than what the doctors themselves get.

At the same time, the medical system is crushing the parts of the job that doctors love: connecting with patients, helping people in need, and practicing medicine as best they can. The system rushes doctors between patients, straining relationships and increasing the possibility of mistakes. It penalizes those who can’t afford healthcare and leaves them with debt that follows them forever. For patients, all of this erodes trust in the medical system, which makes it even harder for doctors to help. Furthermore, physicians feel forced to spend their time with hours of paperwork and computer systems while administrators scrutinize their decisions at every turn. The medicines they prescribe and the specialists they refer to are limited by insurance networks. What’s worse, doctors are on the front-lines of the healthcare system, while those imposing all of this on them hide behind the curtain like the Wizard of Oz.

Like boiling frogs

While doctors have begrudgingly accepted the system that they must work within, resentments continue to simmer. Doctors feel trapped and burned-out. There is no escape from the system unless they quit the profession altogether. So, they grind on, working long hours at a job they no longer love. They hope that something will change, but knowing that it probably won’t. How and why did they let it happen?

This is the classic story of the frog in the boiling pot. If you toss a frog into a pot of boiling water, it will quickly jump out. But if you put it in a pot of cool water and then slowly turn up the heat it will not notice until it’s too late. Most doctors feel ill-prepared to deal with the sharks of corporate business. They focus on caring for people, and they are scientists. They were busy trying to do their best at doctoring, while the heat was slowly being turned up on them.

Learn

Learn Read Stories

Read Stories Get News

Get News Find Help

Find Help

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share