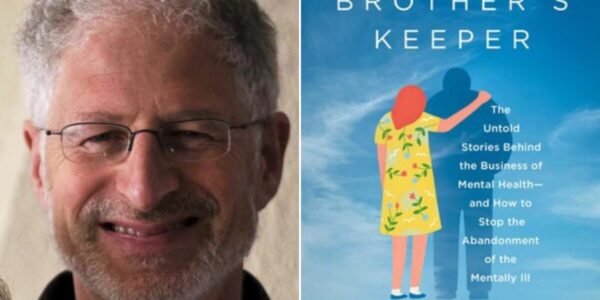

In part 2 of the fourth episode of the Psyched for Mental Health podcast, Dr. Jeffrey Barkin continues the discussion on how COVID has torn apart American society.

In the second half of a two-part episode Dr. Barkin talks about decreased workforce participation and communicating as a health professional in a time of hyper polarization. He also explains his self-prescribed “survival tool kit,” a list of 5 simple things that bring one joy that can be accomplished each day. One of the five things must be a “social reach out,” an easy process to decrease stress by connecting with another person on a daily basis.

Episode Transcript:

The following is not intended to provide direct medical psychiatric or substance use treatment advice, and is not a substitute for evaluation and treatment by a healthcare profess.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Hello, I’m Dr. Ed Bilotti. And this is Psyched For Mental Health, empowering you with trustworthy information about modern psychiatry. This podcast is a companion to WebShrink.com, the platform for seekers and providers of mental health. Welcome to part two of my conversation with Dr. Jeffrey Barkin. In part one, we discussed the psychiatric effects of COVID, long COVID, and the psychosocial aspects of how we as humans deal with catastrophic threats.

In general, we looked at how the virus affects our bodies and brains biologically in this second. We will continue our conversation by exploring the psychological effects COVID has had on us. The role of medical doctors in the media and Dr. Barkin will graciously share with us his toolkit for coping with stress and preventing burnout.

So let’s continue. So the lesions quote unquote, in the brain from these inflammatory responses resemble the effects of those lesions, resemble those of a traumatic brain injury, presenting with brain fog and concentration difficulties, some impaired, um, executive function, perhaps, and fatigue. What about psychologically?

Dr. Jeffrey Barkin:

Boy. I’m so glad you brought that up. So we talked a little bit about the sociology and a little bit just now about the biology, but the psychology is profound because what we see is that patients who develop COVID usually get fearful. People are wondering what’s gonna happen to them.

That’s normal. And most people do well. Nowadays, most people with treatment do really, really well, but there are some people that don’t and some people develop new onset mood disorders. I’ve seen some patients with onset anxiety and depressive disorders, but the big one, the big one to keep your eye on is loss.

We just passed on May 23rd, the million American death mark, that million person count is an eighth the size of New York city, including all of its burrows. So that’s a large number, but let’s maybe take a step into the psychology here because one of the things that I do to start my day when I have a cup of coffee, I read the obituaries.

And when I read the obituaries, there’s usually one or two. Really, you know, touched me, but it made me realize that when somebody dies, a lot of people go, yeah, maybe with me. Oh, you know, he was, he was a nice guy or, you know, something nice, but on average nine people are deeply impacted when one person dies, meaning children, significant others, spouses, parents close friends. Nine.

So for any one of us to die, nine people will be profoundly affected. The effect of that can lead to intense bereavement grief, depression. And more recently we’ve seen because we’re now two and a half years into this, the emergence of a novel diagnosis called Prolonged Grief Disorder.

Now that we’ve had enough people experience enough loss, we realize that the dimensions of bereavement and depression are greater then that what we’ve known, we used to think that when somebody died, that after a year of grieving that they should be back and be better. But what we’re seeing now are people who have lost close ones within their magic circle of nine and who are having ongoing and profound grief responses, sometimes sense of non-existence an existential void.

And the problem is there is a lack of responsiveness to antidepressants in many of these cases. So it’s great that DSM-V-TR has included prolonged depressive disorder, Prolonged Grief Disorder as a diagnosis, but the treatment for it remains obscure. So we’re gonna need time to figure out what is the best way to help somebody who’s lost a close person.

And when you think about that, 10% of people in bereavement develop Major Depression. And major depression is the second leading cause second, only to back pain for decreased productivity. Again, the impacts on the workforce will be profound.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

It’s really powerful how the mental health system can kind of be there and, and absorb, this and be there for people and help people get through this post COVID.

I mean, even if the pandemic were over, which a lot of people I think are walking around with a, a sort of fantastical belief that it is while it really isn’t. Uh, but even if it were over and when it is over that there’s going to be this profound fallout from a mental health perspective and that it isn’t just, okay, that’s over now. We’re all back to normal.

Dr Jeffrey Barkin:

This is gonna take many, many years to get out of whether you’re a child trying to develop normal social cues, intelligence, learn new words, have consistent daycare where you’re learning social cues in person that’s been profoundly interrupted. Parents have had to deal with challenges, raising their children and children have had to deal with challenges, becoming adults and becoming older children that we’ve never even imagined before.

People who are dating have had to completely rethink when that first kiss, that first handshake, that first hug occurs. People that are older, who are sick. Nursing homes have been isolated. People who have been in intensive care units have been saying their goodbyes to loved ones on iPads. The level of isolation and despair is profound.

And to think that it’s going to magically go away is simply magical. The other, the other factor here, and I don’t wanna be depressing, cuz I think that we gotta pivot to some positives, but the other thing that’s happened across everything, in our society is decreased workforce participation. What I mean by that is, is that I we’re in Maine recording this and in the COVID two and a half years, we’ve lost about half of the psychiatric workforce in the state of Maine.

Psychiatric physicians have left practice. And the number one reason that is, is cuz of demographics. We’re an older bunch. Back in 2014, there were four psychiatrists over age, 55 for every psychiatrist under age 55. So that was back, you know, eight years ago. COVID hit older, people are more vulnerable to getting COVID.

So more of the older crowd left the workforce. And interestingly, the stock market did really, really well before this year people’s portfolios went up. So some older physicians were able to retire. Left the workforce, 50% of the psychiatrists leave and yet rates of depression, anxiety disorders go up 40%, rates of substance abuse, 30 to 40 to 50%, depending upon what you, you look at, rates of completed suicide, just sore.

And this drives in the period of COVID. It drives. I think Ed, and I’m curious what your thoughts are from the psychology of isolation and loneliness. And we know from a really good study published a few years ago in health affairs magazine, that the effects of isolation are equivalent to three quarters of a pack of cigarettes per day.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Wow. What an interesting statistic and a unique way of looking at it, powerful stuff. I, and we are gonna to something more positive in a minute, but I wanted to, the, the topic of, of this conversation was not going to be about, uh, about this, but I wanna just kind of bring this up and maybe touch on it a little bit.

And, and maybe you and I can have another conversation in the future going into more depth about this particular topic. But what I wanted to say was to your point about. The increased need for mental health services and the decrease in supply available of people, professionals to provide that service and with the sort of hyper speed that telehealth became implemented during COVID, telehealth was not new. The technology was there, zoom existed for years, but it was not widely accepted. And it was, it was pretty limited with COVID it seemed in six months we advance 10 years worth of, you know, at light speed, suddenly everybody was adopting telehealth and everybody, all of a sudden zoom became, became a household word for better or for worse.

I’d like to know your thoughts about that, because it seems like now that it’s here, it’s here to stay. Even when COVID is behind us. Is it good, bad? Is something lost, uh, from, from having an in person face to face visit with your therapist or with your psychiatrist. And even more concerning to me is the emergence of these seemingly Silicon valley tech companies that are backed by, you know, big money, uh, investors likely and offering what seems like a kind of, I mean, I remember when I was a resident, my residency training director saying if all you’ve ever eaten is fast food, then you never really know what good, wholesome, nutritious food is. And my, and that was the, he, he was making an analogy to managed care, you know, shorter visits.

I don’t think he could have ever even imagined in his wildest dreams that we’d have apps where people could pay a monthly subscription fee and get connected with a quote unquote therapist, somewhere else in the country. And, and that would be how they would be getting their mental health treatment. So I’m a little fearful that if we’re headed in that direction, that people are going, going to be living on a diet of fast food, mental health.

Dr Jeffrey Barkin:

I think that that’s been going on though for a long time pre COVID. First of all, I, yeah, I’d love to talk tech, but I think that before tech and before COVID we had managed care and managed care, made the five star restaurant into burger king and McDonald’s. So once managed care divided the psychiatric community away from doing psychotherapy and just doing medication, we no longer were in a, a quality restaurant. We’re now in a fast food restaurant.

And when I say fast food, I mean fast. I mean, when I see a patient in my practice, my follow ups are a minimum of a half hour. In a clinic practice it’s fast, it’s eight minutes, in a internet based practice, it could be faster. So the speed issue arose before and I believe is separate from technology and I I’m of the mindset of quality or quantity, pick one,

To your question about technology good or bad. I think it’s not reducible to good or bad. I think it’s actually. Maybe we could talk about some of the positives and then some of the negatives. In terms of positives, the work, psychiatric workforce has almost always been an urban workforce. It’s very difficult to get people to go to rural parts of this country, or even rural parts of states that have big cities.

So that’s created a terrible access issue for people in most counties. The use of telepsychiatry and telemedicine in general has been a wonderful level. It’s made it so I can see my patients in any state that I’m licensed in. I’m licensed in three states. I could see patients in those three states. Of course they can come and see me in my office, which I prefer, but I see technology as in addition to live.

So my sense of the future is that we’ll have a, both model, a hybrid model. Hopefully this is my, my take, where we’ll be able hopefully to see patients live. And also see them using technologic forms or collect information using technologic forms that may guide treatment that don’t require that they be seen.

Right. So I can imagine in assessing people for insomnia using smartphone or smart watch apps that do actigraphy and measure activity rather than asking somebody how well they sleep. So I see a role, but I don’t see that companies like Cerebral can replace us. So cerebral.com is a company that came into the space and basically is a telepsychiatry company.

And the problem was that they were prescribing Adderall and stimulants and other scheduled drugs with very, very short assessments. And there was great concern raised and pharmacists, and this is very recent just in the past couple of weeks began to refuse to fill those prescriptions. So I think that, you know, we have to be aware of the risk of misuse too many fast hamburgers, too many burnt French fries, so to speak, but at the same time, the use of technology allows us to fill access issues that previously were just voids.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

So in light of the fact that so many people have been impacted by COVID and probably huge numbers of people who haven’t even sought any kind of mental healthcare are kind of walking around, struggling with some of these things, privately or alone or within their own families. Can you suggest any strategies that people can use to prevent stress or burnout?

Dr Jeffrey Barkin:

Absolutely. Thank you for asking that question. I have been doing more and more corporate seminars and speaking on this, just cuz I’m a psychiatrist and I work in a tech company, a fairly large tech company and a lot. The things that we speak about are very abstract. So when we use terms like mindfulness or relaxation, people don’t really know what they mean.

So early in this COVID misery, I came up with a survival toolkit, which is somewhat concrete. It’s not psychoanalytic. So if your listeners are looking for insight, they’re gonna be sorely disappointed in my toolkit, but, but here it goes. And, and I, I will tell you, I live by it. So it’s, it’s got a few components, but basically it is making a list of five or six things that are simple that you like, and they can’t rely on others.

So no dependencies, if it’s taking a jog, it’s taking a jog on your own. It’s not taking a jog with a friend. It’s not taking a jog with your partner. If it’s, uh, something else, it has to be doable and achievable. And one of them has to be connecting with. Another person. So make a list of five or six things. And one of them is connecting with preferably by phone or in person safely. Another person.

The instruction is simple. Once you have your list of five or six things, all simple things, I’ll fess up and share that one of mine is having a, a dessert, a cozy snack, chocolate bar. I have a hot tub. That is one of them. I have a Pilates reformer. I have a radio show. So each of those for, and, and I like to work out.

So each of those is a point and one of those has to be a reach out to somebody else to just connect socially with somebody. And the goal is to do two or three of those things each and every day, where one of those things is that social reach out. And I have found other people who have found who’ve given me feedback that that has been very helpful because it’s concrete.

It’s easy. It’s simple. It doesn’t require a lot of thinking. It just requires maybe a t-shirt and sneakers or a spoon and some dessert. And given the stress that we’ve all been under, everybody has been under stress. That was unimaginable. That if you’re gonna have a, a more stressful day and it’s one of those days, that’s gonna be worse than usual instead of two or three, make it three or.

And that’s, that’s pretty much the Dr. Jeff psychological survival guide, and it’s so simple. And I’ve yet to find somebody who says that, that hasn’t been helpful.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Great advice, and simple enough to implement. So thank you for that.

Dr. Jeffrey Barkin:

My pleasure. It is simple advice and it is doable and we do a bad job of caring for our psychiatrists and other healthcare providers are all good taking care of others, but life is a marathon, not a sprint. And if we don’t care about ourselves and take care of ourselves, we do fall apart. And we’re seeing this in our community of caregivers. We’re seeing a problem. We’re now, one in five physicians and two in five nurses is planning to leave practice in the next year or year and a half.

So I think that those of you listening, who are healthcare workers and wanna do something that may protect you from a little bit of burnout, maybe that that’ll be helpful.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

So, what, what would you say about the role of physicians say in media? I know there are prominent almost celebrity physicians, like, um, Dr. Oz, and then there are physician reporters, like, um, Sanjay Gupta, just to name a couple that come to mind. And I, I know that throughout the COVID pandemic, there were a handful of physicians who were regularly speaking and commenting on the news media about COVID and, and details about it. What can you say about the role of physicians in the media and how that’s impacted this pandemic and what it should be, or shouldn’t be.

Dr Jeffrey Barkin:

Physicians are uniquely poised and placed to be useful in sharing information with the media. We understand this, but we have to adapt when we are in our consulting room with a patient. Our approach with that patient depends on that patient and our approach with a media outlet means that we have to understand the audience and how to communicate with that audience.

But physicians are generally well respected. We’re generally well liked despite the vitriol and the news that you hear about public health officials or Anthony Fauci or this or that, generally speaking people when they get a physician to talk to are pleased. They’re really happy because physicians, well, we help people.

We help with their health and we help them lead happy, healthy, and productive, and hopefully lengthy lives. So we have to be trusted and get out of our siloed role as thinking of ourselves as better. A doctor in media has a totally different skill set. So the way that I may speak when I give grand rounds or give a presentation is gonna be vastly different than when I’m on the radio or doing a TV piece.

You mentioned some really amazing speakers, but there are others that are out there that have a whole lot less recognition. That didn’t make your list, but who I think of as incredible rock stars like Eric Topel, who is the editor of Medscape and Abraham Verghese, who’s a master storyteller. And the two of them have podcasts.

One is called Medicine in the Machine, which is the two of them. And Eric Topel, of course, does one on one. And it’s kind of created a need for physician communicators. You’re doing a great job with your podcast, bringing information to others. And I think we need to really have a forum for physicians to be trained.

I could tell you that I fell into this role. It was not a purposeful let’s go and do COVID on the radio thing, but it was working in a big company. It became clear, so and so was having a panic attack. So and so was admitted to a psychiatric hospital that in my role as a psychiatrist, that you didn’t need to be my patient.

I didn’t need to give you a prescription. I didn’t need to do anything other than to be able to talk to you individually, or then as a group of people within a division. And then as a group of people within a company of 15,000 or within a broadcast on a network station. The point is that we have to hone how we speak, hone our messaging and be willing to do it.

You know, the biggest fear that people have is speaking in front of other people. The joke is that at a funeral, the person that’s in the worst is the one giving the eulogy, not the person in the box. And I think that us doctors would do a, a good service to the profession of helping other doctors that wanna communicate and become effective communicators do so.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Yeah. Great, great advice. And it’s true. Doctors aren’t necessarily always associated with being great communicators. It’s often been a complaint of patients, you know, uh, you don’t, they don’t, they don’t talk. They don’t listen. They don’t explain. They, you know, uh, have no bedside manner and so on. So there’s that.

Dr. Jeffrey Barkin:

And also our field psychiatry. I’ll take a little swipe at our field. Okay. We get a little, we get a little weird and our words get a little weird. Our words get misappropriated words, like. Paranoid or narcissistic. So and so is depressed, that we, we try to think in terms of a little bit more clarity, a psychiatrist, but we have to appreciate that the general public doesn’t.

And I remind myself every time I do something in media that the way I speak is gonna have a direct impact on somebody or often many people’s behavior. And I think that physicians or educators, we have to acknowledge that role. And quite honestly, sometimes that means doing things like practice.

Volunteering getting on local boards, becoming trusted, known in your community so that other people can just interact with you and get to know you and know that yep. You’ve got their backs that physicians really are not elitist snobs, but people that care about our neighbors and wanna speak the truth and do.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

I just wanna tie something you said earlier in with this, because when you mentioned earlier that as physicians, we’re not always the, the bears of good news, we’re, we’re often delivering bad news. People are coming to us when they’re sick or they’re suffering. And you also just said that many people, you know, people like doctors and people welcome the opportunity to, to speak with a doctor, but it’s not unheard of.

And there’s a whole psychological process. That takes place when the doctor becomes the kind of container for all of the anger and hurt and rage and et cetera at when someone has an illness that can’t be treated or when someone is lost and families can direct a lot of that towards the doctor or the medical profession.

And I wonder also how that is connected with the way Dr. Fauci became a kind of a target or, and a villain. Did he represent sort of the face of COVID and, and therefore have to be the. Everybody’s dartboard.

Dr. Jeffrey Barkin:

It’s very hard to be angry at a virus you can’t see. It’s very easy to be angry at a person you can see.

And I think you’re referring to the concept of projected anger, where we’re angry, we’re upset, we’re distressed. We can’t really put that on a concept like leukemia or having lung cancer. But we certainly can be angry at the bearer of the bad news. We certainly can be furious at the messenger. And we’ve seen that during COVID we’ve seen a true example of that in Fauci.

So how do we respond to that? I was at the American Medical Association annual meeting. Actually the first one in several years in Chicago, just the other week. And I could tell you that one of the discussions I had over and over with doctors from every state were doctors being attacked by patients who thought that COVID was a hoax.

I have spoken with physicians who have to recruit and retain doctors, but their doctors are quitting because they’re being assaulted or being spit upon. There was a case that the American Medical Association litigation center got involved in regarding the state of Montana. The state of Montana wanted to pass a law, making it illegal for doctors and nurses and hospitals to ask patients if they were vaccinated or to ask them to wear masks, we’re not allowed to ask.

Meanwhile, the doctors and the nurses are the frontline, frontline workers. A couple of ER, physicians had apparently asked patients if they had been vaccinated. And in response to that, the attorney general dispatched police to arrest those doctors. Well, fortunately the American Medical Association litigation center intervened and prevented the arrest, but you can imagine being arrested for asking one of your patient if they’re vaccinated or if they’re allergic to penicillin or taking their temperature.

So this is a big, big cause of burnout. And I, I will tell you that the doctors and nurses in Montana, a large number of them were ready to leave Montana. Had that happened and that would’ve precipitated a public health crisis in Missoula and all other parts of Montana.

And, and this would’ve been that it would’ve precipitated such a crisis that fortunately the litigation stopped the arrest of those two physicians. But the physicians all over the country are absolutely burnt out. I’ve had to take several physicians out of work and place them on disability because of this phenomena.

It’s a real phenomena. We have to be kind to our caregivers. We’ll tell you that I have lost several friends who are physicians from COVID, including two people who are very healthy people. And the most sad part is interacting with their young kids and their spouses to the present day. So it’s very real.

And how do we, as physicians, respond to patients when they’re enraged at us? Because they don’t like what we’re saying? Well, that’s another chapter for another show, but that’s something that we learn in our training. What we don’t learn in our training is how do we communicate with a patient who’s so hyped up on a political message and it’s that kind of media training and that kind of communications training where doctors who wanna do that.

And I really encourage doctors to do that are best served, getting a media coach and a mentor. I, myself actually have two people that I’ve identified as mentors. They’re professional broadcasters, because messaging is everything. And what we think of is, you know, the old joke, two psychiatrists walk past each other in the hallway, and one says, hi, and the other says, hello.

And they’re each thinking, huh, I wonder what they meant by that. So we have to become that’s a good one. Good, good communicators. So that when we’re delivering the, the correct message, we’re also engendering the right feeling.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Well, Dr. Jeff Barkin, this has been very enlightening and brilliant conversation, not just a healthy conversation.

So I really appreciate your time and your insights. And I hope that we can get together again to have another conversation about technology or any number of other topics.

Dr. Jeffrey Barkin:

I would love to join you again and thank you for having me. This was great.

Dr. Ed Bilotti:

Thank you for listening. This podcast is a companion to WebShrink.com.

Visit WebShrink.com where you’ll find original, trustworthy, and authoritative content to help you find the answers you need about mental health and addiction, mental health professionals, and facilities. List yourself in webshrink’s provider directory. Go to webshrink.com and click list your practice.The Psyched For Mental Health podcast was written and produced by Dr. Ed Bilotti, co-production and sound editing by Nathan Tower and Aaron Devo at Non-Sensible Productions in Portland, Maine.

Learn

Learn Read Stories

Read Stories Get News

Get News Find Help

Find Help

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share